More Is Better: the Dose-Dependent Effect of Exercise on Health and Longevity

Research has confirmed that government guidelines maximize the benefit to longevity for each hour spent exercising.

Governments and health care providers tell us that we should eat a specified minimum amount of fruit and vegetables and take a particular minimum amount of exercise. But given that these recommendations mean changes – perhaps sometimes ones we’d prefer not to make – in our daily lives, how far can we trust them to deliver longer and healthier lives for the effort we’re being asked to make?

It seems that we should take the guidelines on exercise very seriously. Scientific studies show that the widely adopted target – for at least 150 minutes a week of moderate intensity exercise (see Box below) – maximizes the return on our effort. Just meeting this benchmark decreases the risk of premature death by an average of almost a third. Increasing physical activity still further has an even greater impact, but the Physical Activity Guidelines appear to represent a “sweet spot” in gaining the most benefit for a given amount of exercise.

The Physical Activity Guidelines – The Best Return On Your Effort?

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommends that every week adults should do 150 hours of moderate intensity or at least 75 minutes of vigorous intensity exercise, or some combination of the two. They should also do exercises to strengthen muscles on at least two days a week.

Another way of thinking about this target is in metabolic equivalents, or METs, a measure of the energy used by the body. One MET is the oxygen used while at rest, and exercise can be thought of in multiples of this resting metabolic rate. The exercise recommended works out at 7.5 metabolic-equivalent hours per week.

Moderate intensity exercise could be walking at 3 mph. That’s considered to be 3.3 METs, so two hours of that in your week would bring you to 6.6 metabolic equivalent hours. Vigorous intensity exercise would include running at 6 mph (think of it as completing a mile every 10 minutes). Doing that for just one hour a week would take you to 9.8 METs, arriving more quickly at the 7.5 MET minimum suggested in the guidelines.

When the 150 minute moderate intensity exercise benchmark was investigated in a study led by Arem Moore from the National Cancer Institute it turned out to be remarkably well chosen.

Dr Moore and his colleagues pooled data from several earlier studies in order to mimimize confounding factors distorting the relationship between exercise and mortality rate. Collectively this research included data from more than 660,000 adults who’d been questioned about the duration and intensity of their exercise. What he found was that when it comes to exercise, the more the better.

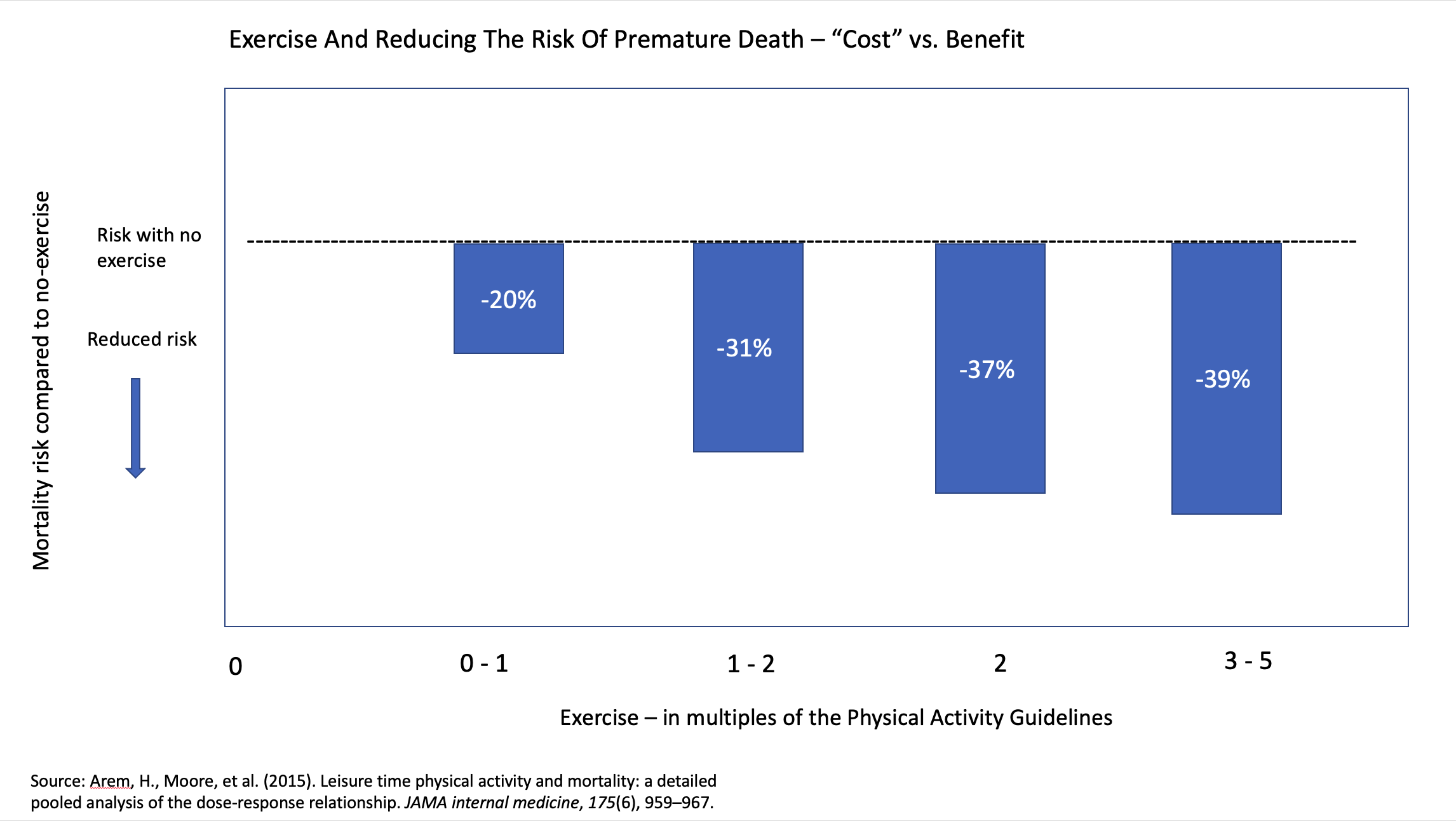

It turned out that people who exercised but somewhere short of the 7.5 metabolic equivalent hours suggested in the guidelines nevertheless lowered their risk of premature death by 20%. However, those whose physical activity fell between 1 and 2 times the suggested minimum had a 31% lower risk than people who’d never exercised. Increasing exercise to between 2 and 3 times the benchmark reduced people’s mortality risk by a further 6%, to 37% below the risk of people who’d always been sedentary. Further exercise increased the benefit but only by a little: exercising 3 to 5 times the rate suggested by the guidelines reduced the risk of death by another 2%, to 39% below that of people who didn’t exercise at all.

There has also been research into the effect of physical activity on the risks of some of the individual diseases contributing to “all-cause mortality”. One interesting example used data from the long-running Harvard Nurses’ Health Study to examine the relationship between exercise levels and a disease that might at first seem to have little to do with physical activity – cancer of the colon. The study monitored 83,000 women over a period of 24 years, and found that those who did exercise of 21 MET hours a week (more than two hours of running at 6 mph) had half the risk of colon cancer as those who did only 2 MET hours (about 35 minutes of brisk walking). Once again, these were associations of exercise rates with cancer risk rather than proof of cause and effect, but given the scale of the study the link between them is clearly a strong one.

It seems that the guidelines set by the Department of Health and Human Services in 2008 provide an optimal “cost-benefit” outcome for exercise: they maximize the benefit to longevity and health for a relatively modest exercise effort. It’s worth pointing out, however, that to reduce the risk of mortality by 31%, a sedentary person would have to do between one and two times the amount of exercise suggested in the guidelines. They therefore represent a minimum amount; more is better. The study found that although the benefit of exercise peaks near the recommended guidelines, further physical activity is unlikely to hurt you. There was no evidence of harm at 10 or even more times the benchmark set by the guidelines.

Exercise And Reducing The Risk Of Premature Death – “Cost” vs. Benefit

The more exercise you take the further you’ll reduce your risk, but the guidelines represent excellent return on effort.

This leads to an interesting reflection on the human body, and the way it has evolved to be adapted to almost constant movement. Physical activity far exceeding the guidelines is the norm for which our muscles, heart and circulation, brain, nervous system and immune system have been finely adapted over time. It’s only in very recent human history that we have reduced out bodies’ movement to what amounts in many cases to a virtual standstill. No wonder simply sitting for too long at a desk produces an increased risk of early death from factors including damage to the arteries, increased blood fat, decreased HDL “good” cholesterol and impaired sensitivity to insulin.

The sobering background to Dr Moore’s findings is that around 80% of American adults and adolescents do not meet the guidelines for physical activity. Increasing exercise by even a little would bring disproportional benefit to many people. It represents low-hanging fruit in the effort to improve health and longevity; the trouble is that too few people are harvesting it.