We Have a Hundred Trillion Little Friends

We Need to Keep Them Sweet if They’re to Keep Us Healthy

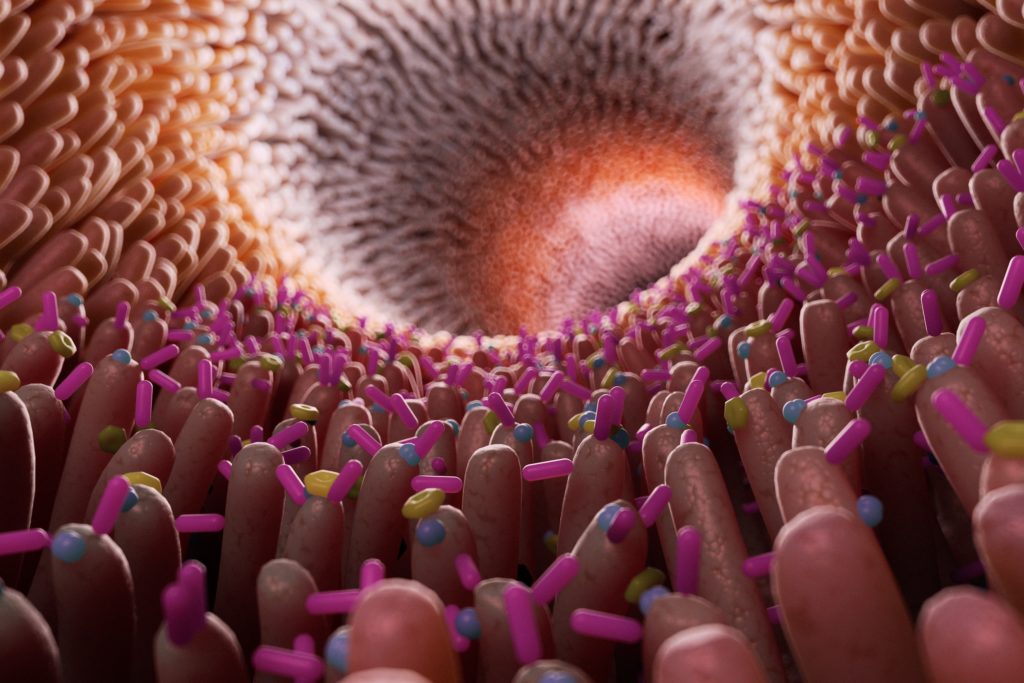

In the average person, they weigh one or two kilos, are composed of around four thousand different species, and number a hundred trillion members. They are the bacteria in our guts.

Evidence is multiplying that this huge workforce plays a critical role in our health, especially in avoiding obesity and the diseases caused by the needless activation of our immune systems, also known as inflammation.

Obesity, associated with “western” diets containing a lot of saturated fat and sugar, and and with more highly stressed and physically inactive lives, is affecting an increasing proportion of the population – even those in their teens and twenties.

Along with growing rates of overweight and obesity, diseases connected with the processing of food such as diabetes, and inflammatory conditions such as cardiovascular disease, are taking an increasing toll.

You might not have recognized gut bacteria when you’ve come across them in the past, but you can’t miss them. These tiny organisms – barely a thousandth of a millimeter long – make up a third of the solid material in our stool. A single full-stop on this page could contain hundreds of thousands of them, and there could be tens of millions on a finger-tip. But collected in our feces they’re impossible to miss.

The microbiota, which includes viruses, fungi and other micro-organisms along with bacteria, live mostly in the colon, the last main section of the intestines. Although the gut – or the gastro-intestinal tract as it’s often known – is housed entirely within us, it actually represents as important an interface with the outside world as our skin. As we send down material from the outside world – food and drink – it carries with it potential pathogens that could threaten us in the same way as the skin is the first line of defense on the outside of the body. That gives our gut bacteria what might almost be described as a vital role in helping us to determine what is dangerous and what is not.

One of the reasons bacteria can serve this purpose in our bodies is that they have evolved with us. We have adapted to their presence in the gut just as they have adapted to us, as we, and they, have struggled to optimize our chances of survival.

It’s a symbiotic relationship built up over millions of years that we disrupt at our peril.

A mind of their own

Collectively our gut bacteria have almost four and a half million genes, compared with our own tally of 21,000. So perhaps it’s not surprising that they have a mind, and an agenda, of their own. They want a warm, moist environment with a constant supply of nutrients, and we have grown to embrace them because their presence has made us healthier and stronger.

A host of immune cells within the wall of the gut keep constant touch with the bacteria passing through, and, based on what they find, trigger the release of hormones that can make us feel hungry or full, or change the way we absorb or process the fats, sugars and proteins in our food.

The bacteria themselves carry proteins that can encourage the production of the mucus that protects the gut wall from pathogens. They can also induce cells in the wall of the gut to tighten or loosen the gaps between them, preventing or allowing the passage of fecal matter into the bloodstream. This controls what has become known as “leaky gut”, and can have profound effects on the level of damaging inflammation we undergo.

Thirdly, bacteria can convert carbohydrates we either haven’t digested or are unable to digest ourselves into tiny fat molecules, called short-chain fatty acids, which have beneficial effects both in the gut and elsewhere in the body.

Our part in the deal

But these benefits come only as part of a personal deal each of us has with our hundred trillion friends. Our part of the bargain is feeding them with the carbohydrate fiber – also known as “prebiotics” – they need.

It works roughly like this: those carbohydrate fibres which humans lack the digestive enzymes to digest, remain intact as they pass through the small bowel where most of the rest of our food is absorbed. In the colon – the last section of the intestines – they encounter bacteria equipped with the tiny protein devices called enzymes capable of breaking them down. These, largely beneficial, organisms multiply in number, signalling to our immune systems to dial down inflammation, nurturing the gut wall, enhancing its mucus protection and tightening it up to prevent any seepage of fecal material.

Beneficial bacteria – such as Bifidobacteria, Roseburia, Eubacterium rectale and Akkermansia muciniphila – rely on a constant supply of prebiotic fibre to displace counterparts such as Escerichia coli and various forms of Streptococcus and Staphylococcus that have the capacity to induce illness or are associated with obesity. Health authorities generally recommend that men and women under 50 consume 38g and 25g of dietary fiber respectively every day for optimal health. Some people are achieving that target, but in the United Kingdom the typical intake averages only about 15g.

Fiber comes in two main categories, soluble and insoluble carbohydrate fibers. Insoluble fiber is the sort that can stay solid in the gut all the way from one end of the alimentary canal to the other, and, among other things, has the effect of toning the gut and keeping it well lubricated. It includes the bran coating whole grains such as wheat and the firmer cellulose and hemicellulose parts of vegetables such as kale, cabbage and broccoli. Soluble fiber mixes with water in the gut to produce a kind of gel, and comes in a range of fruits, vegetables, grains, nuts and seeds, which once made up much of our diet, but which have become greatly reduced in some western countries. Like insoluble fiber, this gel-like substance passes through the small intestine undigested, but once it reaches the large intestine – the colon – it feeds the beneficial bacteria on which we depend so heavily.

What about topping up your beneficial microbes simply by consuming them directly? Some products – such as yoghurt, kefir, kimchi and sauerkraut – can provide beneficial colonies of bacteria together with fiber or a medium likely to improve their chances of success.

But many people choose “probiotic” supplements, tablets or capsules containing millions or billions of “good” bacteria. Apart from the question of the quality of such products, even these large numbers are but a drop in the ocean of the trillions already established in our intestines. Given the extremely rapid rate at which bacteria can multiply by themselves in the right conditions, you can probably make a far bigger difference with “prebiotic” carbohydrate fibers.

The power of pooh

Not everything is known about exactly how our friendly bacteria work their magic in our colons, but the evidence that they have a profound effect is overwhelming.

Studies have shown that obese people have bacteria that are able to harvest more of the calories in their food than people with leaner bodies. This was neatly demonstrated by a study in which obese adults who were overfed – with 3,400 calories a day – and the caloric content of their stood examined. Obese people retained more of the extra calories in their food than a comparable group of normal weight who excreted them in their feces.

When the bacteria contained in an obese person’s stool are transplanted into rodents, it can make the animals obese too. Feces from twin pairs – one of whom was obese and the other lean – were transplanted into mice bred to have no gut bacteria of their own. The mice given feces from obese twins became overweight themselves, but those who got microbiota from lean twins did not.

Bacteria from a lean and healthy donor can actually improve the health of people. An experiment found that transferring microbiota from the intestines of lean people into those with incipient diabetes improved their ability to process sugar healthily.

How do they do it?

Particular bacteria have been shown to play specialized roles in the gut. For example, an organism called Akkermansia muciniphila has been shown to stimulate the gut into producing more of the mucus coating that protects it against organisms and particles capable of causing disease or triggering inflammation.

Researchers have shown that lower levels of Akkermansia are associated with obesity and diabetes, but more of it in the gut can reduce the sort of obesity that comes with over-eating, and improve the way sugar is processed by the body as well.

More light has been shed on the mechanism by which some beneficial bacteria help us stay healthy. Scientists have found that many bacteria – including the Roseburia, Eubacteria rectale and Akkermansia already mentioned – produce short-chain fatty acids such as butyrate, acetate and proprionate. These tiny molecules – consisting of short chains of carbon atoms with hydrogen atoms attached to each one, and an “acid” group at one end – directly nurture gut cells and trigger a reaction in special receptors in the gut wall, stimulating the production of hormones including Peptide YY and Glucagon-like Peptide -1 or GLP-1. These hormones use nerve fibers, and travel in the bloodstream, to signal to the key regulatory centre in the brain, the hypothalamus, reducing our feelings of hunger.

Research has also confirmed that fiber plays a direct role in prompting this bacterial response. One study showed that the consumption of 16g of either of two particular prebiotics every day for two weeks, was enough to increase production of PYY and GLP-1. Another showed that the carbohydrate inulin – contained in vegetables such as artichokes, asparagus and leeks among many others – had the effect of reducing production of the “hunger hormone” ghrelin.

Another hormone whose production is stimulated by “good” bacteria is Glucagon-like Peptide – 2. An experiment on obese mice showed that increases in GLP-2 led to a tightening in the connections between cells in the gut wall, preventing inflammatory molecules from seeping through. Butyrate from bacteria also induces cells in the gut wall to produce a signalling protein called Transforming Growth Factor-beta, which is turn activates anti-inflammatory T-cells and calms down the immune system.

Other mechanisms by which our microbiota enhance our health include their processing of bile acids – a fatty substance produced by the liver – so that they trigger another set of receptors in the colon that produce GLP-1. Beneficial bacteria also produce an acid environment in the gut, inhibiting the growth of the kind of bacteria capable of causing illness.

Can we manipulate our microbiota?

It’s not who you are, but what you eat.

Another famous study – carried out by Pittsburgh University in 2015 – provided an even clearer warning. Twenty middle-aged African American men and twenty similar men from rural South Africa, swapped diets. The African Americans had diets dominated by fast food, eating three times as much fat as the South Africans. The South Africans – for whom a typical meal might be porridge and the vegetable-dominated dish phuto pap – ate five times more fibre than their American counterparts.

The South African men, like the Kenyan children, had a large proportion of beneficial Prevotella, whereas the American microbiotas were dominated by more problematic Bacteroides. Bacteroides, though generally harmless or actively beneficial while contained safely within the gut, are quick to cause disease if they escape this environment and have distinguished themselves by their resistance to antibiotics. Whether it’s a result of differing gut bacteria or not, African Americans are thirteen times more likely to suffer colon cancer than their rural African counterparts, despite their similar genetic profiles.

The results of the swapped diets were startling. After just two weeks, the bacterial populations of the two groups changed dramatically, and so did the health of their colons. As the African participants adopted a highly processed and fatty diet, their production of anti-inflammatory butyrate dropped rapidly and their colons became inflamed. In addition, a wide range of beneficial bacterial products was interrupted to the detriment of their health.

It’s a lesson people eating a “western diet” might take to heart, but it also sounds has huge implications for Africans who are steadily giving up the diets that have been keeping them healthy. With the move to cities and greater prosperity, the proliferation of supermarkets, and the influence of western food companies and their advertising, exposure to high fat, low fiber and processed food is increasing.

Similarly, when Africans – or anyone else – moves to a western country, their children typically take on the increased risks of disease of their new environment, rather than that of genetically similar cousins back home. In the case of Japanese migrants to Hawaii, it took just one generation to lose what had been a low risk of colon cancer.

But there’s a sunnier upside to this story. As the African Americans left behind their burgers and fries and embraced the fiber-filled diet of rural Africans, the health of their colons dramatically improved. In a matter of days, the plant-based diet had radically overhauled those hundred trillion passengers and recruited them in the battle against obesity and disease.